The Association I

Okay, it’s time to come clean: I foolishly hated to admit it in the past, but I’ve always secretly had a warm spot for the Association’s sweet pop and rock music.

The group’s hit songs may at first listen appear too sugary — a heavy dose of pop rock that hit the airwaves in 1966 and 1967 when so many Baby Boomer listeners pined for a new love or an unrequited one. It just wasn’t cool in some teenage circles back then to admit one liked the Association’s songs.

Why? Because, at the same time, the Beatles were releasing their masterful trifecta of albums— Revolver, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Magical Mystery Tour — and the Rolling Stones were releasing Aftermath, Between the Buttons, Flowers and Their Satanic Majesties Request. And rock overall was turning toward a harder edge with bands like the Doors, Jefferson Airplane and Buffalo Springfield getting radio airplay.

But every time the radio played “Along Comes Mary” and “Cherish” — the two blockbuster hits on the Association’s debut album, And Then…Along Comes the Association — it was often impossible to not sing along. Yes, it was great pop music filled with gorgeous six-part (or more) harmonies. There were echoes of the Beach Boys and other pop and folk acts in some harmonies, but the members of the Association undoubtedly put their own stamp on the music. They also occasionally dabbled in garage and psychedelic rock on their albums.

The Association sold a ton of records, headlined in concert over the Who and many of rock’s biggest names and opened the legendary Monterey International Pop Festival in June 1967. And make sure you are sitting down for this one: The band’s six original members may have been the founders of folk-rock and may have handed Bob Dylan the first electric guitar he played in public. (I’ll talk more about all this later.)

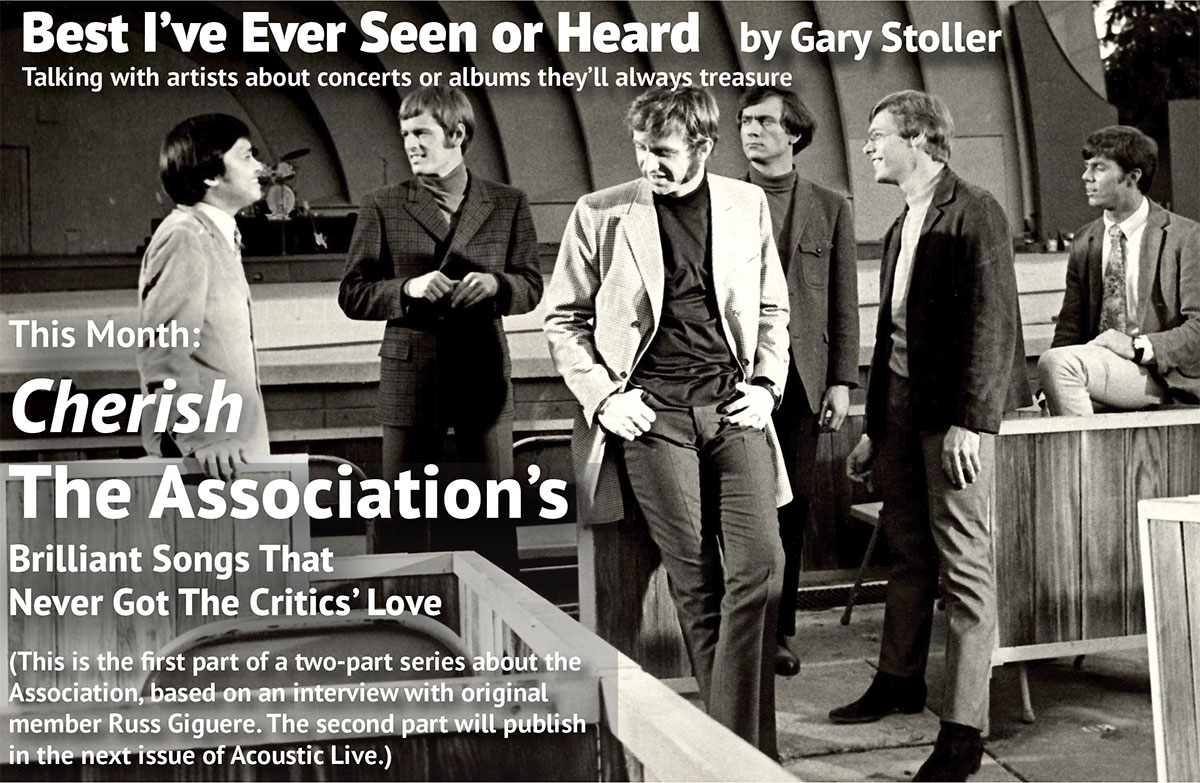

The six original members were Jules Alexander, Jim Yester, Brian Cole, Russ Giguere, Terry Kirkman and Ted Bluechel. Alexander left the group in 1967 and was replaced by Larry Ramos, who was formerly with the popular folk music group, the New Christy Minstrels.

Alexander made the Association a seven-man band when he returned in 1969, and he and Yester still perform in the group with Ramos’ brother Del, Cole’s son Jordan, guitarist Paul Holland and drummer Bruce Pictor.

A year or so ago, a music collector in California mailed me his recording of an Association concert at the Greek Theatre in Los Angeles in August 1970. The sound of the audience recording is quite rough and primitive, but I was flabbergasted when I recently finally listened to it. The Association rocked its head off on several tunes and simply delivered an exhilarating rock show.

I now realize that, unlike the Beach Boys, who received endless praise for their pop songs and harmonies, the members of the Association didn’t get their due from the pundits. The facts: The Association sold more than 70 million records, including six gold records (at least 500,000 copies sold), and had three No. 1 hits and four other Top 40 hits.

Three of the Association’s songs were listed as the most played BMI-licensed songs of the 20th Century. “Never My Love” was named No. 2, “Cherish” No. 22 and “Windy” No. 61. (The No. 1 song was “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin,’” first recorded by the Righteous Brothers in 1964.) The Association was the first rock group to play the venerable Greek Theatre in Los Angeles, and the band received nominations for seven Grammys and one Golden Globe award.

Unlike many other blockbuster 1960s groups, all members of the Association sang on every song. Yet, unlike those other groups, none of the Association’s members became a household name with the general public.

Yester sang the lead on “Along Comes Mary,” and Kirkman and Giguere (pronounced jig-air) sang the lead on “Cherish.” Ramos sang lead with Giguere on two other big Association hits — “Windy” and “Never My Love” — and remained in the band until a heart attack forced him to leave briefly in 2012. He rejoined the group three months later and performed live shows for the next two years until his death at age 72 in April 2014.

Kirkman wrote “Cherish,” and the other three big hits were written by songwriters outside the group. Tandyn Almer, who also co-wrote with Brian Wilson the Beach Boys’ “Sail on, Sailor” and “Marcella,” wrote “Along Comes Mary.” Ruthann Friedman wrote “Windy” while living at David Crosby’s Los Angeles house, and she sang on the Association’s hit version. Dick and Don Addrisi wrote “Never My Love.”

To put the Association’s long-running career in perspective, I interviewed Giguere, who insisted I read, before writing about the band, the 2020 book Along Comes the Association that he co-authored with Ashley Wren Collins. Giguere, who played rhythm guitar and percussion, left the group in 1970 and recorded a solo album, Hexagram 16, before rejoining the band in 1979 and playing in it through 2013. He has since handled the band’s business matters.

I first ask him how he describes the Association’s music.

“At the time, I thought we were just another rock ‘n’ roll band,” Giguere answers. “But now when I look back, it’s this weird, sort of, art rock ‘n’ roll. It’s really hard to bag it. We definitely did some good ol’ rock ‘n’ roll, some ballads and some of the other stuff that was strictly art. So, I can’t really classify it. I’ve never really cared about what the critics say — the people love us, and we love them.”

In his book, Giguere writes: “Being labeled as ‘sunshine pop’ pisses me off…The term was clearly coined by people who are not musicians. We made art, and we made it well.”

Giguere says sunshine pop bands don’t sing about marijuana or soldiers dying, pointing to the Association song written by Kirkman, “Requiem for the Masses.”

Red was the color of his blood flowing thin

Pallid white was the color of his lifeless skin

Blue was the color of the morning sky

He saw looking up from the ground where he died

It was the last thing ever seen by him

The federal government tried to discourage radio stations from playing the antiwar song, Giguere writes in his book. The 1967 song — the final track on the Association’s third album, Insight Out — was inspired by the “call-and-response chorus structure” of Dylan’s “Who Killed Davey Moore?”

Two years earlier, six members of a 13-member Los Angeles group called the Men — managed initially by Doug Weston, the owner of the Troubadour nightclub in Los Angeles — left that group and founded the Association. In 1964, the Los Angeles Times had reviewed the Men’s club show with the headline “Folk-Rock Introduced in Loud, Lively Event.”

Many rock historians, however, have credited my all-time favorite band, the Byrds, who formed the same year, with inventing folk-rock with their debut single “Mr. Tambourine Man.” The Byrds added electric instruments and rock and roll to Bob Dylan’s classic folk song, but they released it in April 1965 — some months after the Los Angeles Times review about the Men.

Another consideration is a media account by Cash Box, a weekly music magazine, in its December 18, 1965, issue.

“It was almost a year ago that we first came across the “Folk-Rock’ phrase emblazoned alongside the door to Doug Weston’s Troubadour on Santa Monica Blvd.,” Cash Box reported. “It referred to the sounds of a group which Weston called The Men…Three of its former members (six is the correct number) went on to become the nucleus for a vocal-instrumental sextet called The Association…The group, incidentally, can perform jazz, folk, rock and roll and folk-rock with equal dexterity. Which brings us back to Doug Weston who started the phrase a year ago. If nothing else, he deserves the credit — or is it the blame? — for that meaty metaphor.”

Besides saying that the Men should be known as the progenitor of folk-rock, Giguere writes in his book that the group lays claim to handing Bob Dylan the first electric guitar he played. Dylan had performed a folk concert in Los Angeles at the Music Box, which later became the Henry Fonda Theatre, and afterward went to the Troubadour and jammed privately with the Men, using one of their electric guitars.

Giguere tells me about another encounter with another one of rock and roll’s greatest names, Jimi Hendrix. Giguere first met Hendrix backstage before the Association opened the three-day 1967 Monterey Pop Festival and then watched Hendrix perform one of the best concerts Giguere had ever witnessed.

“I remember meeting Jimi Hendrix while we were in line to get some grub before we had even heard each other play,” Giguere recalls. “When I first saw and heard him play, it blew my mind. I’d never seen an act like Jimi Hendrix. I was watching from the orchestra pit — just a trio of drums and basic guitar —but spectacular! When he lit his guitar on fire, it was obviously show biz, but it was still great art.”

Hendrix dazzled many a mind at Monterey, the precursor to 1969’s Woodstock Music and Art Fair, which labeled a generation. But others at Monterey also shined. When Rhino Records released its four-CD Monterey box set in 1992, two of the songs performed by the Association were included, “Along Comes Mary” and “Windy,” and the media took notice.

The Orlando Sentinel wrote: “The biggest shocker is pop group the Association. Its lush harmonies weren’t just the product of studio tinkering, it turns out, and aggressive bass lines and a sharp-edge Rickenbacker guitar sound make ‘Windy’ and ‘Along Comes Mary’ sound like more than moldy oldies.”

The Association’s performance, according to the Kansas-based Salina Journal, was “from a time when many critics were dismissing the band as a collegiate knockoff of the Beach Boys, and the ensemble proves to hold its own nicely in the company of such rowdier, born-to-the-stage acts as Canned Heat, Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin.”