“These are very good people. You can talk to these people. They know me well. You can also talk to Peter. He’s old now. Peter goes to Harvard. Peter’s their son. It’s Eve and Mac McKenzie. And they really took me in an’ they were beautiful. Ah, they took me in and I lived with them. And they fed me and it was on 28th St. And I stayed out all hours an’ came in and went to sleep on the couch. An’ Peter was there. I was his idol. At the time he was about 15. Now he’s 18, 19. He’s in college. He’s a very smart kid. Talk to them.”

— The opening quote in Peter McKenzie’s book which he says was part of a 1965 Dylan interview.

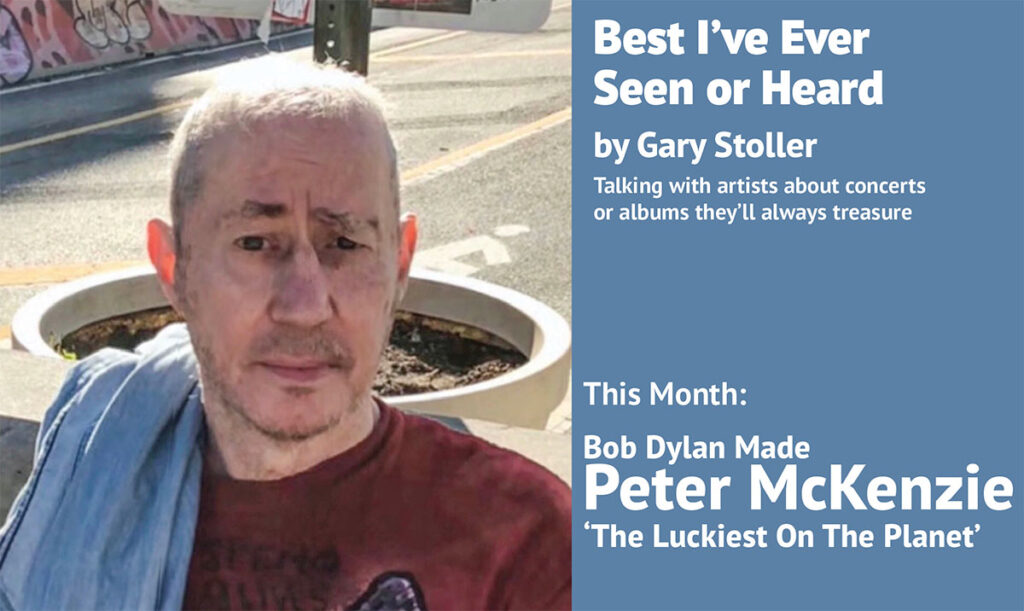

Peter McKenzie believes he was “the luckiest 15-year-old on the planet.” Somebody named Bob Dylan had just arrived in New York for the first time, and McKenzie’s parents let the aspiring folk singer from Minnesota move into their Manhattan apartment.

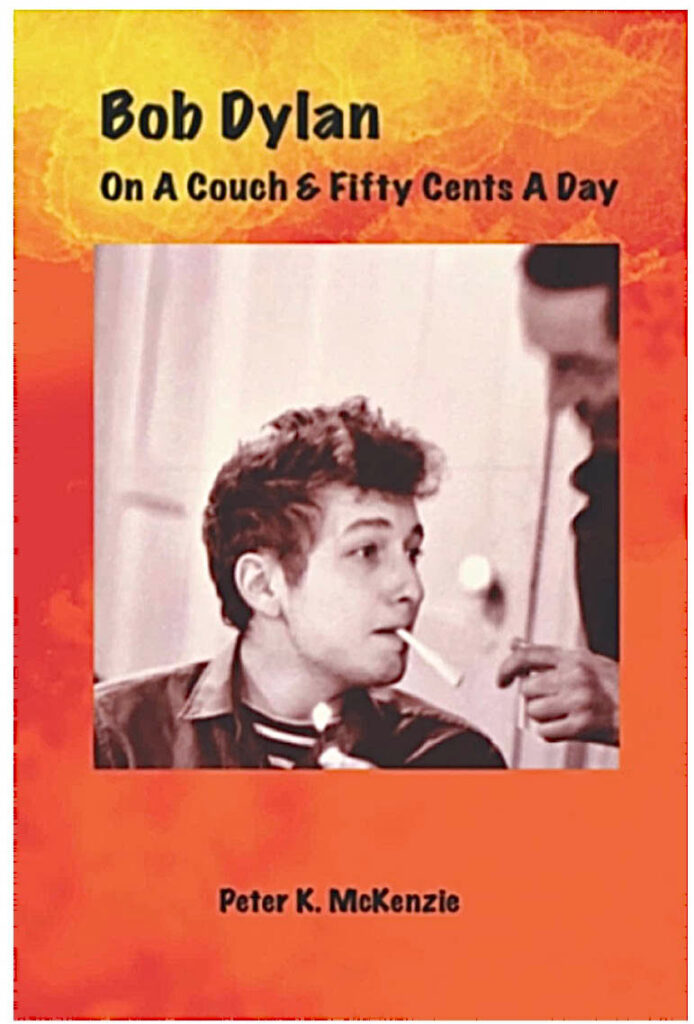

That was May 1961, and, 60 years later, he wrote a book, Bob Dylan On A Couch & Fifty Cents A Day (Amazon link for purchase), about those days together. “It just seemed like the right time” to write the book, McKenzie says.

“I think what pushed me over the edge was when I saw so many books coming out about Bob that were so inaccurate,” he says. “It was cringeworthy. I did read Dylan’s ‘Chronicles Vol. 1,’ and Bob left an awful lot out.”

Dylan’s first year in New York was his most treasured memory, but various happenings became blurry, McKenzie believes.

“That’s only natural,” he explains. “Even with a brain like his, with everything Bob’s experienced in his life, how much can be retained with crystal clarity? So, I guess my book’s a twofer. Not only does it set the record straight for his millions of fans, but it fills him in on parts that may have become a little foggy with time.”

Dylan lived in the McKenzies’ home May-September 1961 on 28th Street between Fifth Avenue and Broadway. He slept on the living room couch except for three weeks when McKenzie went to summer camp, and Dylan occupied his bedroom.

It “was the best place for Bob Dylan,” McKenzie recalls. “It became his own private space where no outside force would bother him, and he could work out all his moves. Every night, his head would rest on the pillow on the living room couch. When he got up, my mother made him breakfast to start his day.”

McKenzie had no brothers or sisters, so Dylan “effectively filled the role as an older brother whom I looked up to and adored.” McKenzie cites Dylan, his father Mac and Dylan’s friend Kevin Krown as “ultimate” influences in his life.

They were “three men I admired and loved who thought for themselves,” he explains. “They were not followers and considered success their philosophy. ‘It’s your life. Don’t let someone else live it for you.’”

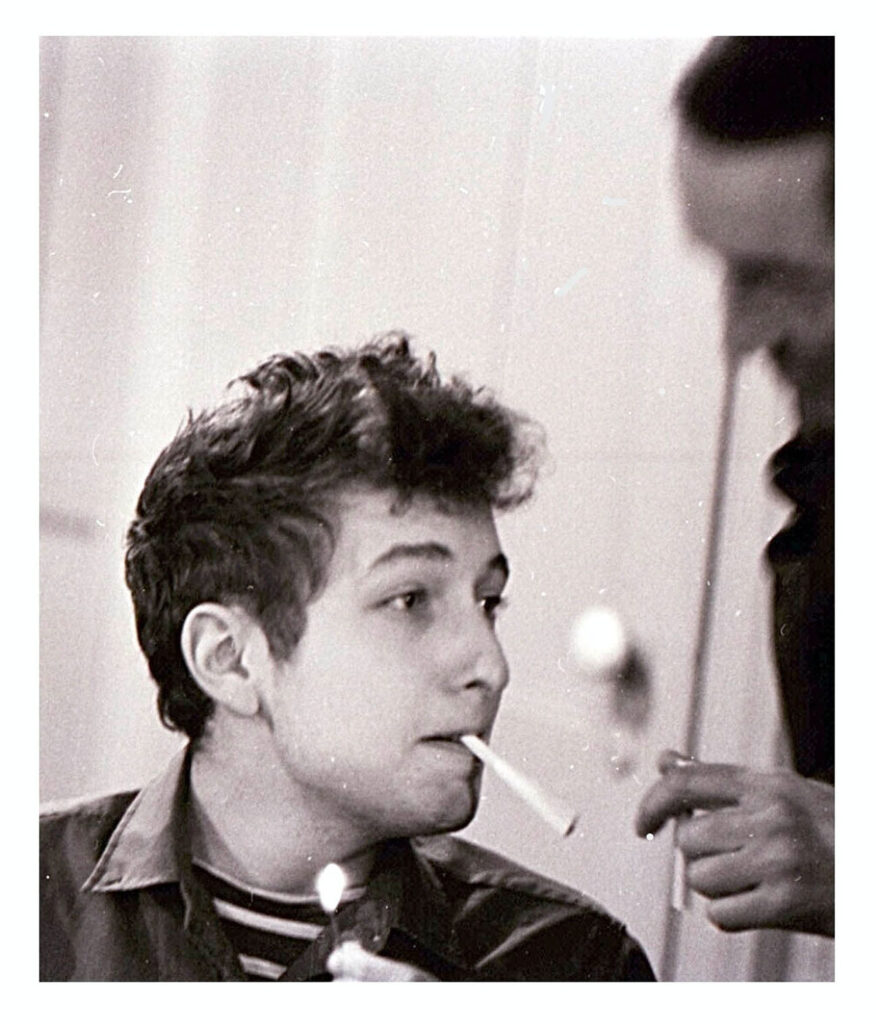

Peter McKenzie first met Dylan in February 1961 at Gerde’s Folk City in Greenwich Village where Cisco Houston, a friend of Mac McKenzie and Woody Guthrie, was performing. Peter became annoyed by the cigarette smoke of a stranger nearby, but then Guthrie’s wife, Marjorie, introduced the stranger — Bob Dylan.

A month later, Dylan and Krown visited the McKenzies at their apartment. Dylan mostly listened and appeared to be sizing up the situation, McKenzie writes. “He seemed to like what he saw, because from that day he, too, started dropping by on a regular basis, with or without Kevin. It turned out he could talk a blue streak when he wanted.”

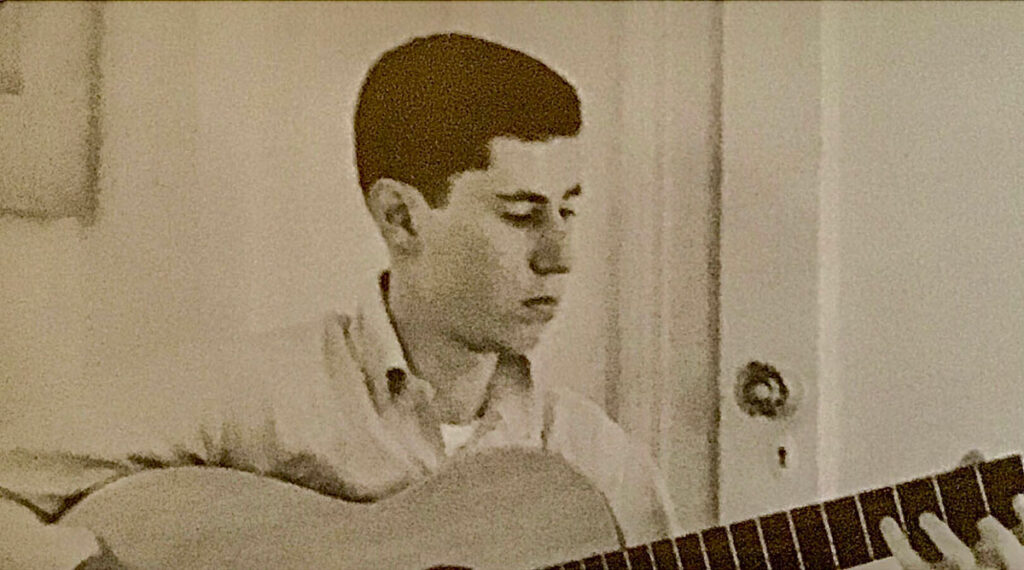

Dylan spent time teaching McKenzie guitar- and harmonica-playing techniques and took an interest in McKenzie’s studies.

“Patiently, he gave me pointers about my homework, particularly my essays,” McKenzie writes. “Truth be told, in private Bob had a perfect command of the English language; his grammar was impeccable. On stage, it was purposely another story.”

In April 1961, Dylan made his paid musical debut at Gerde’s, performing for two weeks as John Lee Hooker’s warmup act.

“John Lee really liked Bob’s hand control over fingerpicking, his syncopation and his interpretation of all southern blues styles,” McKenzie writes. “Bob, when he wanted, could play straight up with the best of them.”

McKenzie believes Dylan’s guitar-playing prowess has been underrated because the focus was on his brilliant lyrics. Dylan, McKenzie says, should have been on Rolling Stone’s list of the 100 greatest guitarists

“If you go back and listen carefully to his guitar playing on his first four albums, from songs like ‘You’re No Good’ or ‘(With) God on Our Side,’ no one plays the guitar like that,” McKenzie writes.

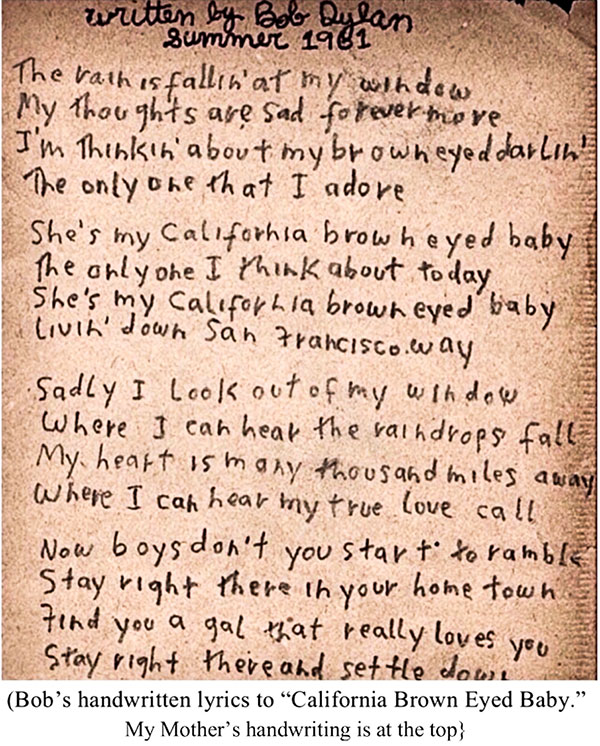

The first original song Dylan sang at the McKenzies’ apartment was “California Brown Eyed Baby” in June 1961, McKenzie says.

“It was also the first song he finished composing since he arrived in New York City,” McKenzie says. “It was for a girl named April he had gone out with, who had returned to her home in San Francisco. He sang it to her over our phone.”

On Nov. 4, 1961, the McKenzies attended Dylan’s concert at Carnegie Chapter Hall on the fifth floor of Carnegie Hall. Dylan visited them three weeks later at a Thanksgiving gathering, and then the family saw him less frequently.

“He would come back and visit on a regular basis over the next two years either to just say hi or seek advice from my parents about what was going on with his life,” says Peter McKenzie, who left New York to attend Harvard University in September 1963. “Naturally, the visits became less and less as the business of his schedule increased and the more famous he became. And then, of course, he got married and started his own family.”

On April 14, 1963, Dylan “dropped by our apartment to see my parents and did the best rendition of ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’ I ever heard for my mother,” McKenzie says. “The cool thing is that it was recorded on tape and is safely stored away, protected and in pristine condition. I am working on a plan to be able to release all the McKenzie tapes made directly from the masters with all the wonderful conversations in between.”

McKenzie tells me he attended many memorable Dylan shows. They include Dylan’s concert at New York’s Town Hall in April 1963; his first Newport Folk Festival appearance in July 1963; Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts, concerts in 1964, and the controversial show at New York’s Forest Hills Tennis Stadium in August 1965 when Dylan and his band departed from his folkie days and began playing electric rock and roll.

Howard Harrison

I ask McKenzie to name the three best songs Dylan wrote.

“That is a question I cannot answer,” he responds. “It all depends on the day and how I’m feeling on that day I listen.”

Okay, but at least name your favorites.

“While I like all his songs, my favorites in the beginning were ‘Talkin’ New York’ and ‘Talkin’ Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues,’” McKenzie says. “I felt I had a personal stake in those songs, because Bob wrote them at our kitchen table while living with us. After those, it’s ‘Let Me Die in My Footsteps’ and ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.’”

“Let Me Die in My Footsteps” is “Bob’s first masterpiece with emotional immediacy and a first-person message from the heart that grabbed your gut,” McKenzie says.

The imagery in “Hard Rain” is “unbelievable, and each line could be the beginning of a whole new song narrative,” he says.

Two more recent favorites are “When the Deal Goes Down” from 2006’s Modern Times and “Girl From the Red River Shore,” one of 27 previously unreleased 1989-2006 songs that were released in 2008 on The Bootleg Series, Vol 8: Tell Tale Signs.

“When the Deal Goes Down” and “Girl From the Red River Shore” are very personal Dylan songs that “reveal what’s really going on emotionally with him with no mask or guile,” McKenzie says. “It’s how he really feels after all the years he’s clocked in life.”

McKenzie says he looks at Dylan “as one member of the family who did it all and conquered the world.”

Is he America’s greatest songwriter?

“Of course, I say ‘yes,’ but it’s hard for me to be objective,” McKenzie answers. “My heart is too involved to let my brain separate out and look at it from an objective viewpoint. There are a lot of great songwriters from the past as well as the present. What is the criteria for a great song? Is it the melody, the words, how it sounds depending on who is singing it? In terms of influence on lyrics in music, there is no doubt in my mind that Bob takes the first position.”

I mention to McKenzie that some of Dylan’s musical friends have said that no one really gets close to the legendary songwriter on a personal basis.

“I clearly disagree,” McKenzie says. “It’s one of the reasons I wrote the book. My parents understood Bob completely and, boy, did he love them. Maybe it’s because we got in early before all the fame hit, and he started trying on different masks. We got him at the core. My parents and I know exactly who Bob is at the core, as much as you can know another person. How much he may have evolved with all the baggage he’s picked up along his own road of life, I couldn’t tell you. We saw the core that’s beneath it all. That’s fine by me.”

What moments spent with Dylan, I ask McKenzie, are most treasured?

“All,” he responds. “I loved the guy then. I love him now. I view Bob differently than most people. To me, his talent is the ability to put words in a certain order, and that’s a great thing. That’s not the reason my parents or I cared about him, rooted for his success and hoped he would attain whatever goal he wanted in life. We cared about him, the person. We’d have loved him just as much and treasured him just as much if he hadn’t made it and wound up a janitor, teacher, accountant or whatever.”