Romantic pain bleeds out of Greg Keelor’s new solo album Share the Love, but that is not a surprise to many of his fans.

Romantic pain bleeds out of Greg Keelor’s new solo album Share the Love, but that is not a surprise to many of his fans.

It’s been a recurring theme for the brilliant Blue Rodeo singer-songwriter-guitarist for many years, so it might be best to call the new release — his seventh solo album — an exercise in consistency.

“Well, you know, it’s a sweet pain, even though it’s devastating,” Keelor tells me from his farm in Ontario, about an hour’s drive east of Toronto. “It’s a pain that connects me to the deeper vibrations of my own place in the world, and it makes me see my place in the world quite differently. It makes me a little more empathetic and compassionate for myself and all creatures in existence.”

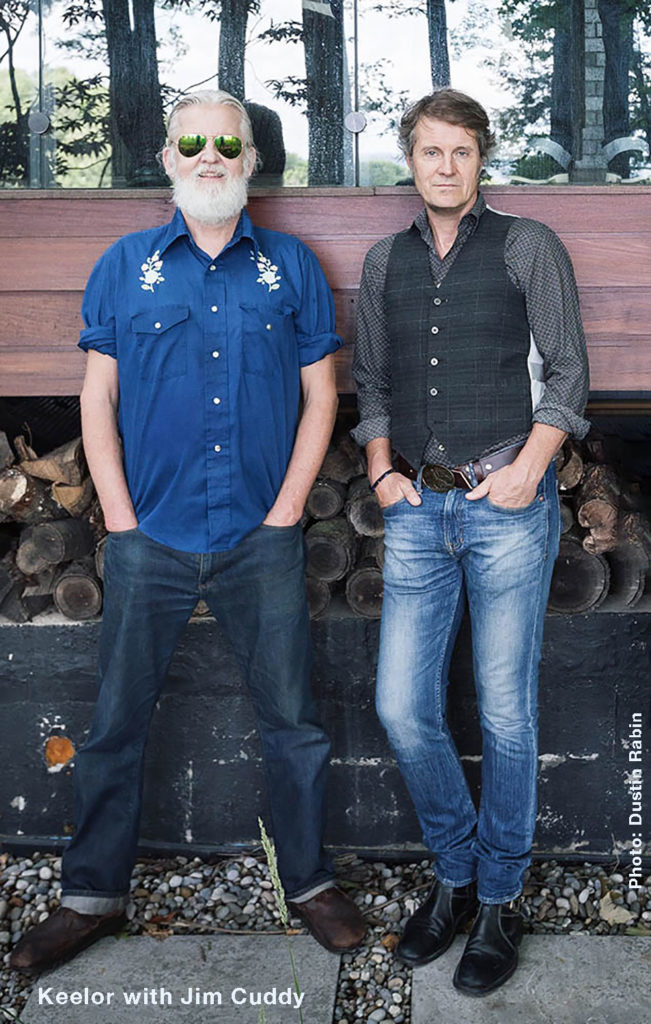

Though many Keelor songs over the years involve heartbreak or carry a dark or melancholic vibe, he has also written many touching, beautiful songs, as well as rock classics like “Lost Together,” often the closing song of a Blue Rodeo concert. He and high school buddy Jim Cuddy, an equally brilliant songwriter, have brought so much joy to listeners and concertgoers since the duo founded Blue Rodeo in the mid-1980s. The group was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame in 2012 and is in the process of recording a new album.

Keelor says he enjoys being happy and celebrating life, but he doesn’t strive to live a happy life, because happiness isn’t everything. Melancholy is also a good feeling, he says. “I like feeling disconnected from the flow of the cultural fiction.”

In Share the Love’s final song, “Goodbye Baby,” Keelor laments:

In Share the Love’s final song, “Goodbye Baby,” Keelor laments:

Why did I believe you

I should have played it cool

‘Cuz now I’m all busted

Broken and blue

Broken and blue

Share the Love was initially an acoustic album with “a Fairport Convention vibe” that was completed before the pandemic fully struck North America. Keelor decided not to release the album until the pandemic abated, and then, as months passed without resolve, he gathered the seven musicians who played on it for a promotional video. Keelor liked their electric versions of the songs so much that he scrapped the acoustic album and opted for the new versions.

The album kicks off with a great one-two punch with the songs “White Dove” and “Black Feather.” “White Dove” is about the first guitar he played which “set off a reverberation inside of me that I’ve been chasing ever since.” The song switches gears near the end with a guitar break that could fit on the Beatles’ Abbey Road.

“Yeah, I guess at the end there’s a little bit like the Beatles,” Keelor says. “They are hardwired into my being. My parents moved in the mid-1960s from Toronto to the suburban Montreal town Mount Royal where the Beatles reigned supreme. Everybody, including me, was freaking out about the Beatles, and that era of music will always be very prominent in my being. I’ve gone through so many different phases since, but that’s still the structural foundation.”

“Black Feather” is about being “as low as you can be when nothing is working,” Keelor says. “It just keeps getting worse and worse and piling up. But then, sometimes when you’re in that state, one little positive thing can happen, and it changes your perspective. It totally lifts you out of your melancholy and despair. It seems like a personal miracle. It shifts the way you’ve been and the way you’re seeing the world and yourself. And you’re sort of overwhelmed with gratitude.”

The white and black imagery appears to be part of a yin-and-yang force throughout the album, but Keelor says it wasn’t what he was aiming for. There are recurrent images and feelings, he says, and a lot of songs are “meditation patterns.”

Keelor says he was mentally in a dark place when he wrote the songs two years ago. A friend died of brain cancer after spending months in a hospice, and Keelor’s girlfriend broke up with him. But there’s also happiness shared with a new girlfriend, as expressed in the tender ballad “Caolaidhe.”

When I think of you

In my bed last night

With your head on my pillow

Well it gets me high

Makes me want to fly

Caolaidhe

Caolaidhe

Caolaidhe

Caolaidhe

Another high that has been a constant throughout Keelor’s life is his love for the guitar. He says he’s obsessed and fascinated with the instrument — “the sound of those strings chasing the white dove” — despite developing tinnitus that forced him to relinquish his lead electric guitar role in Blue Rodeo.

Another high that has been a constant throughout Keelor’s life is his love for the guitar. He says he’s obsessed and fascinated with the instrument — “the sound of those strings chasing the white dove” — despite developing tinnitus that forced him to relinquish his lead electric guitar role in Blue Rodeo.

“A guitar is such an amazing machine,” he says. “It has done so much to change and affect the culture that it has been brought into. It was a machine used to make a political-social statement and fight fascism during the Woody Guthrie and folk song era. Then it was part of the cultural revolution of the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show and taken to the extremes — psychedelic guitar and Jimi Hendrix.”

I ask Keelor how the tinnitus, which I also developed after a very loud Joe Satriani concert in a small concert hall, has affected his songwriting and music.

“Well, I’ve had it for about 30 years,” he responds. “At first, I thought I was gonna go crazy. It affected so much more than just my hearing — my balance, everything, my head totally restructured itself. Now, I am so used to it, and I think I would miss it if it went away.”

The tinnitus made Keelor feel like he was underwater. He had massive headaches, and touring “became a torture.” But some relief came when Colin Cripps took over his electric guitar duties, and Blue Rodeo made some equipment changes. The technical changes included putting the amps off stage, setting up drummer Glenn Milchem behind a Plexiglass shield and having one monitor on stage for Keelor’s voice and acoustic guitar.

And, surprisingly, the coronavirus pandemic had one positive effect.

“The touring wears my ears and head down,” Keelor says, “but, having this year off from touring, I’ve been able to sit at home, play my guitar, have friends over and work on some stuff. Just to have the time to work on songs, when my head wasn’t in a state of pain or recovery, was quite nice for me.”

Keelor’s guitar heroes include Clarence White, James Burton, Link Ray, George Harrison, Keith Richards, Richard Thompson, Nick Drake and bossa nova pioneer João Gilberto. He says he has been influenced by his peers, though, as much as his heroes. He points to Jimmy Bowskill and Kyler Tapscott, who play on his new album; Blue Rodeo’s Colin Cripps; Canadian bluesman Jackie De Keyzer, and Dallas and Travis Good of The Sadies.

I ask Keelor which concerts he attended that made him say “I can’t believe what I saw.” He immediately points to two Bob Dylan shows at Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens — one with The Band in January 1974 and the other, a year later, with the Rolling Thunder Revue, which included Joni Mitchell, and Gordon Lightfoot.

Keelor also puts a third show at the top of his list: Neil Young’s return in December 2017 to his childhood hometown, the village of Omemee, Ontario, for a solo gig before 225 invited guests at tiny, historic Coronation Hall. Outside the hall, thousands watched the performance on TV screens.

“I’ve met and hung out with Neil a few times over the years,” Keelor says, “and his older brother is a good friend of mine. The old hall in Omemee was built by the guy who built Toronto’s Massey Hall. I went to the soundcheck the day before, and Neil’s music was as beautiful as music can be. It was a dream. I just loved it.”

Both Young and Blue Rodeo have released live albums recorded at legendary Massey Hall, which has been hosting performances since 1894. According to Keelor, Blue Rodeo has performed about 40 shows at the hall, more than any performer except Gordon Lightfoot.

Blue Rodeo’s Massey Hall album was recorded during a 2014 show, but the group’s concert there in February 2017 is considered by the Toronto Globe and Mail as one of the 10 best performances in the history of the venue. For the last song of the night, “Lost Together,” Keelor and Cuddy brought out their friend, Gord Downie, the lead singer of the Tragically Hip. It was Downie’s last show before he died of brain cancer.

That was a bittersweet night, but Blue Rodeo shows are usually upbeat, full of great rock and roll songs and gorgeous harmonies, with concertgoers singing along to many songs. The chemistry between Keelor and Cuddy and the musicianship of the entire band is downright mesmerizing.

So I ask Keelor to explain the musical magic he and Cuddy have created and shared for so many decades. “Well, we’re just such good friends,” he responds. “In 1978, we put an electric band together, and we recognized that our voices sounded great together. We realized we could do stuff with our voices that sort of surprised and shocked us. We could sing a song like the Beatles’ ‘There’s a Place’ and do the harmonies just like the Beatles. When you first start doing that sort of stuff, you’re self-amazed, and you’re amazed at what your friendship with this guy can do. There are times when it’s quite a beautiful sound to hear our voices together.”

So I ask Keelor to explain the musical magic he and Cuddy have created and shared for so many decades. “Well, we’re just such good friends,” he responds. “In 1978, we put an electric band together, and we recognized that our voices sounded great together. We realized we could do stuff with our voices that sort of surprised and shocked us. We could sing a song like the Beatles’ ‘There’s a Place’ and do the harmonies just like the Beatles. When you first start doing that sort of stuff, you’re self-amazed, and you’re amazed at what your friendship with this guy can do. There are times when it’s quite a beautiful sound to hear our voices together.”

Unlike many rock groups who splinter apart, become defunct or rarely tour, Keelor, Cuddy and Blue Rodeo bassist Bazil Donovan have been touring continuously since the mid-1980s.

“We’re just sort of committed to the long ride,” Keelor says. “There’s an old Anne Murray quote that we sort of keep on the top of our stationary: ‘Long-term greed over short-term greed.’”

So many groups, though, who are led by two creative, highly intelligent musicians, either quarrel and break up, or the duo heads for solo careers. How have Cuddy and Keelor managed to avoid such conflict?

“Well, we’ve had our share of fights,” Keelor says. “The love has always outweighed the fighting, and there’s a certain compassion amongst us. And there’s an understanding to let people follow their own musical interests.”