Many great artists were important parts of the influential 1960s Greenwich Village folk scene. Yet, many didn’t get the acclaim they deserved because the spotlight was focused on the incredible talents of Bob Dylan.

The list of artists whose music was never fully heralded is lengthy, and some are still performing today. The list includes such names as Tom Paxton, Dave Van Ronk, Fred Neil, Tim Hardin, Odetta, David Blue, Ian and Sylvia and Patrick Sky.

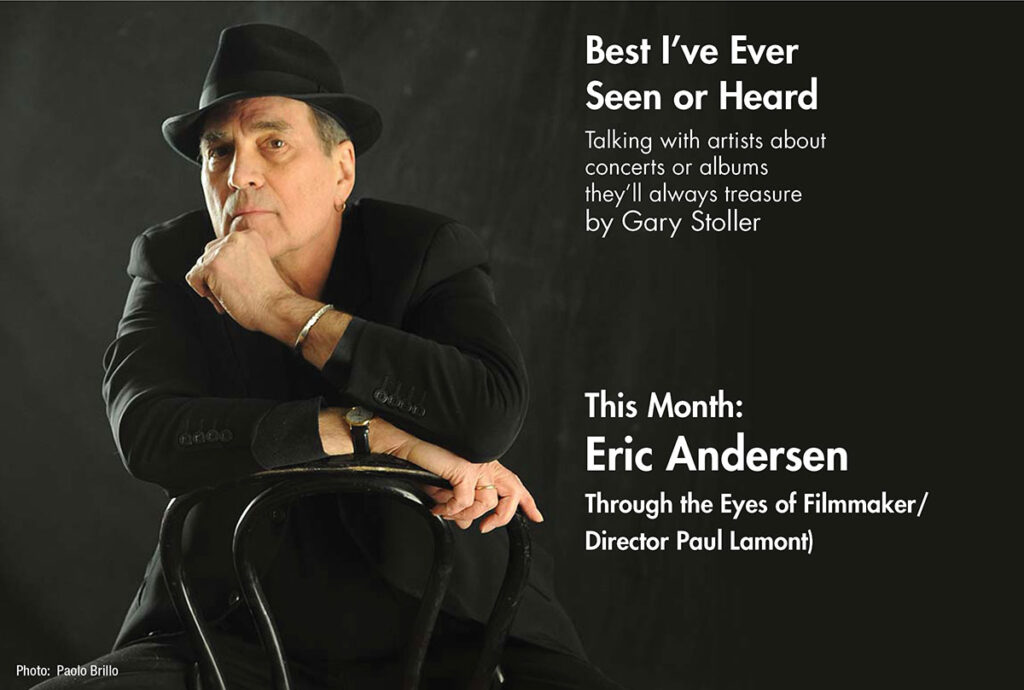

Another notable name belongs on that list: Eric Andersen, one of the world’s best songwriters who released a three-CD set Woodstock Under The Stars in June and is regularly performing and releasing top-quality albums. His brilliant song “Thirsty Boots” was covered by Dylan on his Another Self Portrait album, and two filmmakers, Paul Lamont and Scott Sackett, have completed a documentary movie, The Songpoet, about his life.

They are currently negotiating with PBS and a national distribution company for distribution on Blu-ray, DVD and video on demand and hope to have a deal finalized by the end of the year.

Lamont let me view The Songpoet, and it’s an excellent account of Andersen’s life and music. I have closely followed his career since the early 1970s and first met him during two nights of interviews at Denver’s tiny club, Ebbets Field, in 1974. Between the early and late shows one night, he became fascinated by my recording of the first show, listened intently and asked me to mail a copy to his Woodstock home. I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve seen him perform since, but I’d guess 20-30 shows.

Lamont says he has seen Andersen perform about 15 times and can “vividly recall” the first time he discovered the songwriter’s music.

“As a teenager with little money, I used to shop the bargain bins at the local store,” recalls Lamont who has produced and directed 11 films for national or regional PBS. “One day, as I flipped through the albums with the cutout on the corner, I spotted The Best of Eric Andersen. Having been a fan of artists like Murray McLaughlin and Gordon Lightfoot, I thought ‘this guy looks interesting.’ So, I bought the album from the 39-cent bin and brought it home. The needle dropped on the opening cut, “My Land is a Good Land,” and I was hooked. That best-of double album led me to start looking for any Eric Andersen albums I could find.”

Lamont’s film shines a light on Andersen’s Pennsylvania and western New York upbringing, his artistic development and life in San Francisco, Greenwich Village, Woodstock and Scandinavia, and his friendships with Phil Ochs and other artists. It also explores his family life, including his relationship with his first wife, Debbie Green, a talented folk musician, and his current wife Inge Andersen, a social scientist and singer who has released one solo album.

Aside from the depth and beauty of many of Andersen’s songs, probably the most compelling aspects of the documentary, though, are two unfortunate events that may have derailed his path to mass stardom.

The Beatles’ famed manager, Brian Epstein, died of a drug overdose in 1967, soon after becoming Andersen’s manager. And, after Andersen received critical acclaim for his 1972 masterpiece album, Blue River, which featured Joni Mitchell, 40 master recording tapes for a highly anticipated followup album, Stages, mysteriously disappeared at Columbia Records.

Epstein’s death and the loss of the tapes for Stages were turning points in Andersen’s career, Lamont says.

“There was a ridiculously small window of about five years in the early- to mid-1970s for someone like Eric, who was about to emerge as a credible force in the singer/songwriter genre, to take advantage of before musical tastes went in another direction,” says Lamont, whose films have been nominated for multiple Emmy Awards. “Stages was such a strong album with some of Eric’s finest work. As a follow up to the successful Blue River album, it would have gone a long way to help cement Eric’s position in the singer-songwriter movement.”

The tapes for Stages were found years later, and the album was released as Stages: The Lost Album in 1991.

6″Stages had an intimacy, warmth and sincerity that’s evident in so much of Eric’s music, and, thanks to the great work of producer Norbert Putnam, those qualities were captured and came through loud and clear,” Lamont says.

Lamont’s favorite Andersen album, though, is 1989’s Ghosts Upon the Road. The choice is a surprise to me, because I see no album rivaling Blue River, and I can name many albums I deem superior, including 1967’s ‘Bout Changes & Things, 1975’s Be True To You, 1976’s Sweet Surprise and 1998’s Memory of the Future.

“Like picking a favorite song, a favorite album is tough, too,” Lamont says. “I’d have to say Ghosts Upon the Road for a few reasons. First, in the early ’80s while Eric was in Norway, he put some albums out that had limited release in the U.S., so I lost track of him after he released Sweet Surprise in 1976. Because I hadn’t heard anything from him for so long, Ghosts Upon the Road seemed to me like his return.

“Secondly, his writing had taken on a decidedly different feel,” Lamont continues. “I’ve always considered Eric more of a poet than simply a songwriter, and Ghosts Upon the Road felt like a more literate album than previous ones. The 10-minute title track is a haunting spoken-word performance and not a traditional song. It’s a profoundly personal narrative of his struggles for survival and sanity, as he takes the listener on a journey through his early and troubled — but defining — years as an artist. So, in some ways, the album’s tonality, which seems to drip with emotion, is reminiscent of Blue River. The album is also punctuated by his life in Europe. The writing is embedded in his new geography in the songs ‘Belgian Bar,’ ‘Spanish Steps’ and ‘Trouble In Paris.’ It was also beautifully produced by Steve Addabbo.”

When I ask Lamont his favorite Andersen song, he coincidentally picks the one that first turned me on fully to Eric’s music. It’s the opening track of Blue River, “Is It Really Love at All.”

“It drags me in,” Lamont says, “from the opening lines: ‘Sitting here forgotten/Like a book upon a shelf/No one there to turn the page/ You’re left to read yourself.‘ The simplicity of the words, the starkness of the imagery of a forgotten book on a shelf and the sense of loneliness that saturates the image, all unfold with such emotional complexity. I’ve come to appreciate the song even more after having had the opportunity to read many of Eric’s journal entries, because, in one entry from 1969 or so, he wrote almost those exact words to describe how he was feeling.”

Many of Andersen’s best songs — “Violets of Dawn” from ‘Bout Changes & Things is a great example — are steeped in poetic imagery. Consider the first two verses of “Violets of Dawn.”

Take me to the night, I’m tippin’

Topsy-turvy turning upside down

Hold me tight and whisper what you wish

For there is no one here around

Oh, you may sing-song me sweet smiles

Regardless of the city’s careless frown

Come watch the no colors fade blazing

Into petal sprays of violets of dawn

In blindful wonderments enchantments

You can lift my wings softly to fly

Your eyes are like swift fingers reaching out

Into the pockets of my night

Whirling, twirling, puppy warm

Before the flashing cloaks of darkness gone

Come watch the no colors fade blazing

Into petal sprays of violets of dawn

Andersen may be the ultimate songwriter for expressing romanticism and sensitivity, while his songs avoid sappiness and remain powerful and poignant.

He can be quite sensitive off stage, too. After his late show in Denver in 1976, a friend jokingly called him “a psychotic,” and Andersen replied, “Call me Mr. Emotional Cripple.” He noticed me jotting down his response, took my pen, crossed out “Mr.” and replaced it with two words: “just another.”

Andersen’s concerts have always worked best when they are intimate affairs, usually in small clubs or small outdoor settings. I remember seeing him with an electric band in New York’s Central Park, and his songs were lost in the noise and hubbub of a large crowd. When you can hear a pin drop, Andersen’s songs can stick you in the heart and mesmerize you.

Lamont has also been mesmerized by Andersen’s live shows, but he cannot name which of the 15 or so Andersen concerts he saw was the best.

“The interesting thing about Eric’s live performances are how different they all are,” he says. “When he performs, he’s not just up there doing the same thing over and over again. Even when he’s doing a song like the classic ‘Thirsty Boots,’ it’s always a different feel or musical approach that gives it a certain freshness.

“When I saw him a couple of years ago, he pulled ‘We Were Foolish (Like the Flowers)’ out of his hat. The song is off the Avalanche LP, a bit of a quirky album released in 1968. When he started the song, I was floored. The timbre of his voice, now deeper with age along with the accompaniment of Eric Lee on fiddle/mandolin, Steve Addabbo on electric guitar and Cheryl Prashker on percussion, was riveting. He also changes up his touring band, too. He’s toured with Scarlet Rivera or Michele Gazich on fiddle and Stephen Jagoda on percussion. That change in lineup gives his music a different feel as well. You can be sure that if you see Eric in concert once, it won’t be the same the second time around.”

Lamont is just as enthusiastic about Andersen’s new three-CD set which provides a window into his artistry nine to 29 years ago. Among numerous live highlights, the album includes two songs at a Norwegian jazz festival when Andersen was one-third of a trio with The Band’s Rick Danko and Jonas Fjeld. Danko and Andersen were close friends who lived in Woodstock for many years, and the tracks were on one of the two excellent early 1990s albums recorded by the trio.

The three-CD set “really showcases the power of Eric’s writing,” Lamont says. “The songs, which cover the spectrum of his career, were recorded at various locations in Woodstock between 1991 and 2011. He makes a song like ‘I Shall Go Unbounded,’ which first appeared on his second album in 1965, seem as if it could have been written yesterday. From the building anger and energy of ‘Rain Falls Down in Amsterdam’ to the floating ‘Down At the Cantina,’ the emotional depths of ‘Sinking Deeper into You’ and the richly textured ‘Eyes of the Immigrant,’ each cut reminds me why Eric is such a timeless artist who writes songs of sublime beauty.”

Though the three-CD set is essential listening, Andersen is not an artist from bygone years. He was born on Valentine’s Day 77 years ago — a fitting date for his lyrical romanticism — but his newer albums are imaginative and challenging. He released Shadow and Light of Albert Camus in 2014, and 2017’s Mingle With The Universe: The Worlds Of Lord Byron is an excellent work that combines Lord Byron’s poetry with Andersen’s muse and music.

With so many unique, creative albums in Andersen’s catalog, I ask Lamont how he views Andersen’s place and significance in music history.

“That’s a big question, because Eric’s music touches me on such a deep level,” Lamont responds. “He certainly has the respect of many well-known artists, and he’s collaborated with artists such as Lou Reed, Townes Van Zandt, Wyclef Jean, Rick Danko, Joni Mitchell and a host of others. He has a strong and dedicated fan base but, unfortunately, hasn’t garnered the attention of that wider audience. In my opinion, Eric deserves to be up there with others who are household names. I feel that he belongs in the pantheon of contemporaries such as Dylan, Paxton, (John) Prine and (Gordon) Lightfoot.”

Lamont reiterates a major point of The Songpoet documentary: how fragile an artist’s career can be.

“Being in the creative world is like skating on thin ice all your life,” he says. “You’re cruising along just fine one day, and, the next, you’re taking a cold and potentially devastating plunge into the icy waters below. I think had it not been for a couple of extraordinarily bad strokes of luck along with perhaps some personal missteps, Eric would have captured that wider audience. I think we’ve all fallen victim to bad luck, bad timing and unfortunate circumstances, but it goes to a bigger question: How do we handle what we’ve been dealt?

“The things that happened in Eric’s career might have devastated others and ended careers, but he pushed on,” Lamont says. “And, as his archivist says in the film, not having the tremendous pressure that often accompanies commercial success has perhaps given him the freedom to stay true to himself as an artist and to create music that he might not have been able to create otherwise.”