Critics savaged Bob Dylan’s 1970 Self Portrait album, but it’s my most-played Dylan release, and there was critical acclaim when an expanded box set of the album was released 43 years later. Are we headed for a similar critical reversal with The Complete Budokan 1978, a just-released four-CD set that expands on Dylan’s 1979 Live at Budokan double album, which was lambasted by some critics?

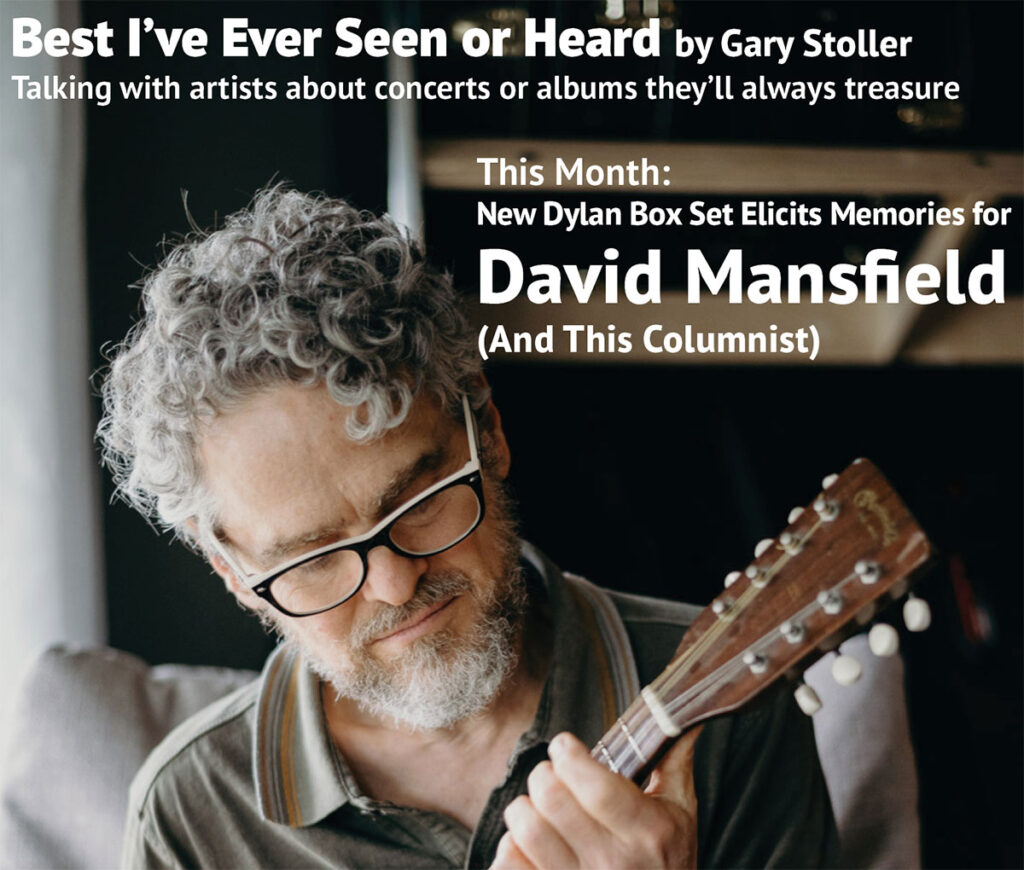

I met Dylan briefly later in the year on that tour, and I recently asked multi-instrumentalist David Mansfield, who played fiddle, mandolin, pedal steel guitar and dobro at those 1978 shows, for his impressions of the music.

My meeting with Dylan was, by chance, on Thanksgiving evening, Nov. 23, 1978, in a Ramada Inn hallway next to a candy machine in Norman, Oklahoma. He had just performed a riveting 28-song concert at the University of Oklahoma’s Lloyd Noble Center, and I had stood inches away from him on the arena floor when the band blasted its thunderous, rocking final song “Changing of the Guards.”

Afterward at the Ramada Inn, Dylan slammed his room door shut and, still in facial stage makeup, walked down the ground-floor hallway and stopped to talk to me and a friend. He was humble and appreciative of our praise for his show. “Did you really like it?” he asked, and he seemed genuinely surprised that we did as he eyed my New York Jets baseball hat. Was he putting us on? I will never know. I drove to Fort Worth for the next night’s show but never again met him.

David Mansfield, though, knows more than I will ever know about the music of that tour and the Budokan album. And he, too, heard the critics.

“They accused him of going Vegas,” Mansfield tells me. “If he did something similar today, though, I can’t imagine there would be a problem with it. Bob wasn’t selling out. He was just trying something different, which is what he’s always done.”

The Live at Budokan tour was a few years after Dylan’s tour with the Rolling Thunder Revue. Rolling Thunder had received critical acclaim in the media, was highlighted by the repeated playing of hit song “The Ballad of Hurricane Carter” on the radio and culminated in a highly publicized Madison Square Garden concert to free jailed boxer Rubin “Hurricane” Carter.

The Live at Budokan tour “couldn’t have been more different from Rolling Thunder, which was very loose, full of improv and quite ragtag at times,” recalls Mansfield, who also was in Dylan’s Rolling Thunder band in 1975-1976. “In 1978, the very large band was made up of first-call musicians, the arrangements were carefully worked out and things were very consistent from one night to the next.”

Dylan was pleased with the entire band’s music throughout the Budokan dates and the subsequent shows in 1978, Mansfield says.

“Budokan was just the first stop on a year of touring,” Mansfield recalls. “Bob had called me up months before to join his new lineup. We rehearsed for months at his studio in Santa Monica before heading out on the first leg, which was Japan and Australia. I think the recordings hold up, but I really wish we hadn’t made the live album at the very beginning of the tour. By the end of the year, we really had bumped everything up a few notches.”

The Budokan shows in Tokyo in 1978 were Dylan’s and Mansfield’s first time in Japan. Dylan performed three shows in late February at the indoor arena that was built for the 1964 Summer Olympics, then did three shows in Osaka and returned to Budokan for five more shows. The expanded new album includes 36 previously unreleased songs and the complete Budokan concerts of February 28 and March 1.

“That year, Bob was in a great mood,” Mansfield recalls. “He joked with the audience, even did shtick. At one point, he was introducing me as, ‘David Mansfield — he’s sweet 16 and never been kissed.’ Bob hung out with the band on the plane and in the bar after the show. I know he had been through a rough divorce. Maybe the year of touring was cathartic for him.”

Mansfield cannot recall the University of Oklahoma show that I attended in 1978, but I mention to him that, after the show, I walked into a Ramada Inn room that was cleared of beds, and band members were very quietly conversing and appeared to be in a prayer session. I quickly exited and later wondered if this might have been the beginning of Dylan’s apparent conversion to Christianity, which culminated in his 1979 album Slow Train Coming.

“There was never a prayer session or Bible study,” Mansfield says. “If Bob was starting to examine Christianity, it was totally under the radar, and the band was completely unaware of it. In fact, we were quite shocked when, at the end of the year, he let the band go and canceled all his 1979 touring dates due to his religious conversion. So was his manager at the time, Jerry Weintraub. When he reconvened and released Slow Train Coming (August 1979), it was with an entirely new band.”

Touring with Dylan in 1978 was a very special time for Mansfield. That same year, the Alpha Band, which included Mansfield, T-Bone Burnett and Steven Soles, released its third and final album, and Ever Call Ready, a gospel-bluegrass group that included Mansfield, Chris Hillman and Bernie Leadon, released its only album.

“Actually, 1978 was entirely taken up by touring with Bob,” Mansfield says. “The third Alpha Band record had been released before touring, and my work with Al (Perkins), Bernie, Chris and Jerry (Scheff) that led to Ever Call Ready was considerably later. So, I wasn’t overwhelmed. It was a wonderful year, spent on the road with Dylan and a fantastic band.”

After the tour, Mansfield became involved in the film Heaven’s Gate.

“The film’s producer, Joann Carelli, had seen me with Dylan at Madison Square Garden, where I got a standing ovation for my electric fiddle solo on ‘All Along the Watchtower.’ That solo had gotten a lot better since its premiere at Budokan, and she made a note to hire me as the on-camera fiddle player in Michael Cimino’s new Western.”

Mansfield spent half of 1979 filming in Kalispell, Montana, as an actor in the film and was given a few lines of dialogue.

Photo: Ivy Ney

“After production was finished and the film went into post, I anonymously sent Michael some four-track home recordings I had made of music that had been sung on camera by actors in the film, in hopes that it might be useful as source music,” Mansfield recalls. “He was in the middle of interviewing composers. He had intended the score to be a big orchestra work and had met with Ennio Morricone, John Williams and others. But, when he started playing with my music against the picture, he completely changed his mind and ended up hiring me to write an intimate Eastern European folk score. That was my introduction to the world of film scoring.”

Thus, a notable film and television musical career began. Mansfield produced the soundtrack albums for various films, including Year of the Dragon, The Sicilian, Desperate Hours, Ballad of Little Jo and Broken Trail. Excerpts from his scores for Heaven’s Gate and The Sicilian were performed at London’s Royal Albert Hall and New York’s Carnegie Hall.

His score for Oliver Stone’s Year of the Dragon was nominated for a Golden Globe award. He also was nominated for an Emmy for the score he co-wrote with Van Dyke Parks for Broken Trail, an A&E mini-series.

Mansfield, a formally trained violinist, has also played on numerous musicians’ albums. I mention to him that I was the only person in a large circle of musical friends who had an LP by his teenage band Quacky Duck and His Barnyard Friends.

“Quacky Duck started out as a local band in Englewood, New Jersey,” he says. “I lived in neighboring Leonia, where my best friend was Tony Bourdain — yes, that Tony — who went to a private school in Englewood with two members of the band, Danny Bennett and Curtis Fried. Tony and I were 15 at the time; he made the intro, I auditioned and joined the band.”

A few years later, the group graduated from local New Jersey concerts, with posters made by Bourdain, to playing at the legendary Manhattan Max’s Kansas City. Quacky Duck and His Barnyard Friends opened at Max’s for Gram Parsons on his only solo tour, with Emmylou Harris in his band.

“Quacky Duck had been signed by Mary Martin — of Albert Grossman fame — to Warner Bros. records, and I still am very proud of the record we made,” Mansfield says. “If one or two songs were a little sophomoric, well, we were actually sophomores! The best writing on the album really holds up, and all the living members of the band are still good friends.”

With Quacky Duck in full swing, Mansfield starting playing with other musicians at their recording sessions in New York.

“It was the early ’70s, country rock was all the rage, and I played fiddle, mandolin, pedal steel and dobro,” he says. “Hardly anyone in New York City played those instruments very well, so I found myself in demand. I did a lot of recording with producers like Cashman & West (best known for producing Jim Croce’s hits) and artists like Chip Taylor, who wrote ‘Angel of the Morning.’ The summer before Rolling Thunder, I was playing gigs with Eric Andersen, having played on his record Sweet Surprise. The band included the late, legendary Richard Bell, Chris Parker and Arlen Roth — first-call players all the way — so I was already quite experienced for an 18-year-old.”

Mansfield got involved in Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue through the late Bobby Neuwirth, a friend of Dylan who was playing four nights at New York’s Other End (originally, and today, called the Bitter End) in Greenwich Village in 1975.

“My girlfriend at the time worked at the Bottom Line (a nearby, now defunct, music club) and heard about the scene swirling around Bobby — guests such as Roger McGuinn and Mick Ronson sitting in and rumors of Dylan sightings,” Mansfield recalls. “One night, she dropped by, noticed that the set was sort of country/folk, and they didn’t have a fiddler. She dragged me down there the next night, waltzed me back to the dressing room and told Bobby, ‘My boyfriend is a great fiddle player.’ He said something along the lines of, “Well, break it out.” I did, and he invited me to join the band on the spot. That run of shows was what, months later, turned into the Rolling Thunder Revue.”

Photo: Joel Bernstein

Mansfield played fiddle, mandolin, pedal steel guitar and dobro in the Rolling Thunder Revue — a traveling caravan of musicians, poets and others who arrived in small cities to play concerts with little advance notice and spawned two Dylan movies. Dylan also saw another fiddler, Scarlett Rivera, playing on a New York street corner and invited her to join the group.

“Although I’m also a guitarist, I didn’t play guitar, as there were already five guitarists — Mick Ronson, T Bone Burnett, Steven Soles, Dylan and Neuwirth,” Mansfield says. “Scarlett and I never played together. When she played with Dylan, I moved to pedal steel or mandolin. But I played violin with Neuwirth, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and others (who also performed songs on the tour without Dylan).”

Martin Scorsese’s 2019 film, Rolling Thunder Revue, includes a scene with Dylan driving a multi-passenger vehicle, so I ask Mansfield if that really happened. The film contains mostly footage of the Revue participants traveling and performing — much of it outtakes from Dylan’s 1978 Renaldo & Clara movie — but also includes fictional content.

“Bob never drove the tour bus,” Mansfield says. “We had a Winnebago motor home. Rather than ride with the band in the tour bus, he rode in the Winnebago and drove that. One time, one of our semis was stuck in the loading dock at the venue, and Jack Elliott got into the cab and backed it out, to the chagrin of the professional driver. Jack certainly could having driven one of our Golden Eagle buses.”

Offstage, Mansfield didn’t spend much time with Dylan.

“I had just turned 19 and was the kid,” Mansfield says. “Bob was mostly cavorting with the more mature members of the ensemble. I did become close, though, to many others, including Bobby Neuwirth, Joan Baez, Roger McGuinn, T Bone Burnett and Steven Soles.”

Mansfield says his most memorable moments with Dylan were “standing transfixed by the side of the stage every night to watch him do ‘Tangled Up in Blue’ as part of his solo set and the raucous fun of his performance of ‘Isis’ with the full band.”

Dylan’s performances of “Isis” during the Rolling Thunder tour, including the one shown in the Scorsese movie, were, arguably, his greatest hard-rocking concert moments. The performances were powerful, gripping and moving, as Dylan defiantly spat out word after word, including the song’s first four lines below.

“I married Isis on the fifth day of May

But I could not hold on to her very long

So I cut off my hair and I rode straight away

For the wild unknown country where I could not go wrong”

Mansfield mentions another “Bob,” though, when I ask him which concert was the best one he ever performed in.

“I would say any one of the Bobby McFerrin “spirityouall” shows,” says Mansfield, who was in McFerrin’s band during those 2013 concerts. “They were musically challenging, playful and unbelievably fun. Bobby just wouldn’t let an audience go home without enjoying themselves.”

According to his website, McFerrin “throws some unexpected new ingredients into the melting pot” and reinvents Americana” with the spirityouall album. And, I guess it’s a small world: The sixth track on the record is Dylan’s classic song “I Shall Be Released.”

Mansfield says the best concert he ever attended when not performing was Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention at New York’s Wollman Rink in Central Park in the late 1960s.

“It was madly eclectic and creative — even for ’60s pop music — and well before Zappa turned to the mostly adolescent prurience of his ’70s work,” he explains.

I ask Mansfield which album is the best one he ever listened to.

“That changes all the time, and I don’t even think ‘best’ is a useful term when it comes to recorded music,” he responds. “So, I would have to go with a safe choice and name Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. I’m a Beatles baby, and I feel that project was their apex — writing, arranging, performing and recording. And on only four tracks!” (using four-track tape machines)