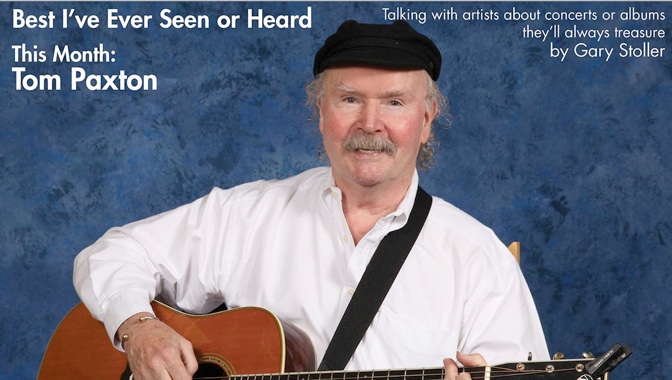

Tom Paxton has been writing songs for more than 60 years, but don’t ask him how many he has written. “I have no idea how many songs I’ve written, and I think it’s largely irrelevant,” says the prolific folk singer-songwriter who celebrated his 82nd birthday on Halloween. “There are hundreds of lousy songs in my work books. The only thing that matters is how many would I admit to having written, and that’s 200 or 300.”

Anyone unfamiliar with Paxton’s songs might be wise to listen to his most recent release, The Essential. The album contains 36 songs, including many with his colorful and often insightful political and social commentary.

Of all his political songs, Paxton cites three as his proudest creations.

“’What Did You Learn In School Today?’ was one of Pete Seeger’s favorite songs,” Paxton says. “’Jimmy Newman’ was my best Vietnam-era song, making the whole horrible mess understandable on a personal level. ‘The Bravest’ (a tribute to firefighters) did the same with 9/11.”

Paxton, who received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2009, says other songs that make him most proud are “The Last Thing On My Mind,” “Ramblin’ Boy” and “On The Road From Srebrenica.”

He says he never gets tired of singing “The Last Thing On My Mind,” which was on his first album Ramblin’ Boy. The song has been covered by numerous artists, including John Denver, Glen Campbell, Johnny Cash, Joan Baez and Judy Collins. Paxton loves the “simplicity and sing-ability” of that song and the album’s title cut, “Ramblin’ Boy.”

Who does Paxton regard as America’s greatest songwriter?

“Oh, I’m just not up to that one,” he responds. “I love so many of them — Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, Guy Clark, John Prine.”

“Every progressive east of the Mississippi must have been there,” Paxton recalls. “The atmosphere was indescribable. We all sat on stage, and I sat next to Bob Dylan.”

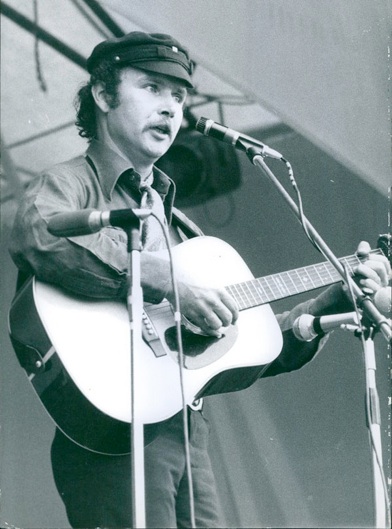

Dylan, Paxton, Phil Ochs, Dave Van Ronk and others were part of the early 1960s Greenwich Village folk music scene. So I ask Paxton to look back at all the music Dylan and Ochs created and tell me his view of their contributions to American music.

“I spent lots of time with each of them,” he says. “I feel their early work holds up amazingly well, but that’s just my opinion. Phil’s scope was much more limited than Bob’s, of course, but he kicked ass with it. I miss him every day.”

Paxton recalls a historic night with Dylan at a room upstairs at the Gaslight Cafe, a Greenwich Village coffeehouse where musicians stored their guitar cases and other belongings. The establishment closed in the early 1970s.

“There was a table and chairs where we had a continuous penny-ante poker game going, and there was a portable typewriter put there by Hugh Romney (later known as Wavy Gravy),” he recalls. “One night, I came in for work and found Bob taking what proved to be the last page of a lengthy song out of the typewriter. ‘What’s up?’ I asked him. ‘New song,’ he said, and handed it to me.“I read it, and it was long and really, really good. ‘It’s ‘Lord Randall’ revisited,’ I said. ‘What do you think I should do with it?’ Bob said. I told him he could send it to some periodical and get paid $25, but he should put a tune to it instead. So, he did, and the next night he sang ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.’ I sang it a year or so ago at a Bob’s birthday concert and enjoyed the hell out of singing it.”

Currently, Paxton enjoys performing shows with the DonJuans, a duo comprised of Don Henry and Jon Vezner. The duo won a Grammy for their song “Where’ve You Been,” which was recorded by Kathy Mattea.

Paxton explains how he began collaborating with the DonJuans.

“I did a lunchtime concert at the Swannanoa Gathering (a folk arts program at Warren Wilson College in North Carolina) a few years ago,” he says. “I knew Jon slightly from Nashville, and he approached me after the show and suggested we write together.

“After we wrote a few songs that I liked, he mentioned he and Don were playing as the DonJuans, would like to open my shows and then play with me. I agreed to try it out and, on the first occasion, at Isis Music Hall in Asheville, I realized after the third or fourth song that these were not sidemen but two-thirds of a trio. I continue to feel that way. I’m having a great time playing, writing and traveling with them. Like all really good partnerships, we are writing songs that none of us would have written on his own, and, yet, they are easily identifiable to me as my kind of songs.”

His politics, though, have always been a part of his music.

“I haven’t changed much,” he says. “I’ve always been pretty much a liberal Democrat, which places me in pretty lonely company these days. Phil was the radical; I’m a Bobby Kennedy Democrat.”

America’s political climate today is “poisonous,” he says. “We have a president appealing to the lowest and vilest corners of his base’s instincts.”

Paxton’s political beliefs may bring to mind the Weavers, the influential, left-leaning 1950s folk group led by Seeger. The Weavers’ second album was a major influence on Paxton’s budding career. The Weavers at Carnegie Hall album “changed my life,” Paxton says. “I first heard it while still a student at the University of Oklahoma in about 1957. In one hearing, I evolved from someone who loved this music to someone who had to do it. It truly set me on this path.”

It’s been a long road since, and Paxton’s songs and live shows have entertained and inspired countless people worldwide.

“I’d like to be known,” he says, “as someone who treasured the legacy of folk music and tried to carry it on in his own work.”