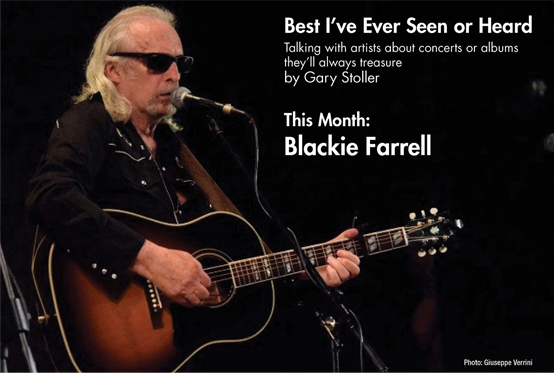

Looking back at his 4-year-old Cold Country Blues album, Blackie Farrell has quite a unique take on the results.

Gurf Morlix and Bill Kirchen “dragged me out of long-term storage, and I left a decent pile of rust in the studio,” Farrell tells me.

Farrell, who says his nickname comes from a black eye “in every grade school picture,” is probably best known for one song on the album, “Sonora’s Death Row.” It’s been covered by Kirchen, Leo Kottke, Robert Earl Keen, Richard Shindell, Tom Russell, Michael Martin Murphy, Dave Alvin and others.

“When I look back at making Cold Country Blues, I wish I could go back and do it again,” says Farrell, who lives outside Oakland, California. “It was that much fun. I couldn’t be more satisfied. My voice, though, is in better shape now, and I wouldn’t mind doing a couple of vocal tracks over again.”

Farrell says he was in the “best of hands” working on the album with musical veterans Morlix and Kirchen. Morlix has 10 solo albums and has played or produced albums with Ian McLagan, Blaze Foley, Lucinda Williams, Butch Hancock, Robert Earl Keen, Mary Gauthier and Ray Wylie Hubbard. Kirchen is arguably the world’s best Telecaster guitarist, a solo artist who was an integral part of Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen and has played with Nick Lowe and Elvis Costello.

“Gurf and Bill have mucho mileage on their collective studio odometers,” Farrell says. “They have deep toolboxes. I told Bill I wanted the record to be baritone-Tele-heavy, and he delivered in spades.

“Gurf knows his stuff and is a multi-instrumentalist. His pedal steel on ‘Mama Hated Diesel’s’ and ‘Jim Donny’s Gold’ still gives me chill bumps! Having Rick Richards on drums, Nick Connolly on piano and B3 and Yvette Landry on button accordion, it was like being driven to school by the Untouchables. I felt I was bulletproof with that team of players and pals having my back. Andre Moran’s steady hand as engineer, and Mark Hallman’s mixing and mastering made for a perfect storm.”

Farrell points out three songs as the best ones on the album: “Mama Hated Diesel’s,” “Sonora’s Death Row” and “Skid Row in My Mind.”

“Mama Hated Diesel’s” was the first Farrell song that appeared on a record — Hot Licks, Cold Steel & Truckers Favorites by Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen in 1972. Kirchen sang that song and shares a songwriting credit.

“It was an A-side single that made the charts,” Farrell says. “I got a bunch of free coffee and pie in truck stops for a little while.”

“Sonora’s Death Row” was “a big deal for me for several reasons,” Farrell says. “As a youth, I was blown away by Marty Robbins’s great cinematic songs ‘Big Iron’ and ‘El Paso.’ The care he put into every nuance, and his masterful coloring of a picture painted with words is a master class in writing — period.”

Farrell says he dreamed of writing a song that would serve as a worthy tribute and honor the inspiration Robbins provided.

“When I lived in Nashville, I was lucky enough to sing ‘Sonora’ for Marty face-to-face,” Farrell recalls. “I was a nervous wreck. He was down to earth, and, to my relief, he genuinely liked the song. It also was the last song I thought would ever be covered by anyone. It was too long for radio back then — no chorus, no bridge and a dead body. But I was proven so wrong, because it’s the most recorded song in my catalog.”

Tom Russell tells me he admires the song, too. He says he needed “authentic-sounding cowboy voices” and “true grit” on his 2015 album The Rose of Roscrae, so he brought in Farrell to sing backup on “CowboyGhosts/Cowboy Voices.”

Sonora’s Death Row is “one of my all-time favorite cowboy songs, and I plan to feature it on an online cowboy concert,” says the prolific Russell whose most recent album is 2019’s October in the Railroad Earth. “Blackie sat in with me in Reno, maybe six years ago, and we sang it.”

The third song Farrell considers as one of his best is “Skid Row in My Mind” — the sixth track on the 11-song album.

“A lot of people, men mostly, tell me that I wrote their story,” he says about the song. “Makes me feel like I did my job. Plus, it has a couple of grownup chords.”

Farrell wrote his first song at age 13 after learning three chords on his first guitar.

“Lightnin’ Hopkins showed me my first guitar chord,” he recalls. “I brought my guitar backstage, and he was in a good mood. I think I was 15 or 16 when I first played any kind of gig. I played with a few other guys, and we had different-named bands that played mostly parties and dive clubs that accepted fake IDs. But then I began focusing on being a writer more than a player. That eventually led me to Nashville, and on my way to making, to quote Robert Earl Keen, ‘hundreds of dollars a year.'”

Farrell has worked lots of other jobs to put bread on the table, including framing houses and working as a pipe fitter.

“I was always on call for anything that paid cash and was legal,” he says. “Royalties used to honestly match sales and airplay, but those days are gone. If you’re not strong of heart and not driven by a passion for stringing words together, then this singer-songwriter game isn’t something I’d recommend.”

Farrell initially met Kirchen in Berkeley, California, in the late 1960s.

“I was visiting a girl who had a huge vinyl collection of classical music,” Farrell recalls. “I noticed a couple of apple crates in the corner full of primo country, blues and folk albums. She told me some guy left them there, and I could have ’em. I was humping the last armload down to my car when this guy pulls up on an old BMW motorcycle and says, ‘Hey pal, where you going with my records?’ After some circlin’ and sniffin’, we became fast friends.”

Farrell met Morlix in Austin but doesn’t recall the year.

“I think we were on the same bill on an outdoor stage, and I introduced myself to him,” Farrell says. “He knew who I was from the Commander Cody record Cold Steel and Hot Licks with ‘Mama Hated Diesel’s’ on it. He told me he was inspired to learn pedal steel listening to Bobby Black play on my song. It was one of those deals where you feel like you’ve known the person all your life. Same species.”

Farrell also could relate to many blues giants he watched in concert and says their shows, as well as James Brown at the Apollo and Aretha Franklin at the Fillmore West, are the best ones he has seen.

“I’ve been fortunate to have gone to so many cool concerts and festivals in my life,” he says. “I saw Big Mama Thornton, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Jimmy Reed and John Lee Hooker — all live, up close and personal, before I was 12 years old. As a young teen at a folk festival in Berkeley, California, I sat within arms length of young Mavis Staples and her sisters and Pop Staples playing his Telecaster with the tremolo cranked. I fell in love with Mavis, the Telecaster and tremolo in one fell swoop.”

I ask Farrell to name his three favorite albums and their influence on his music. I get an interesting response.

“As a writer and a musician, I believe that everything that enters your brain or soul, whether it be through your ears or eyes, is an influence,” he says. “In all honesty, I can’t pick just three favorite albums. If there’s a musical afterlife, and I left someone out, I might get my ass kicked.”