For many years, I have asked musicians which albums are the best ones they have heard. I’m glad no one has asked me the same question, because I would struggle with an answer. I can, though, identify the albums I play the most, and one of them, Mark-Almond 73, digs deeply into my heart and is unknown by most music fans.

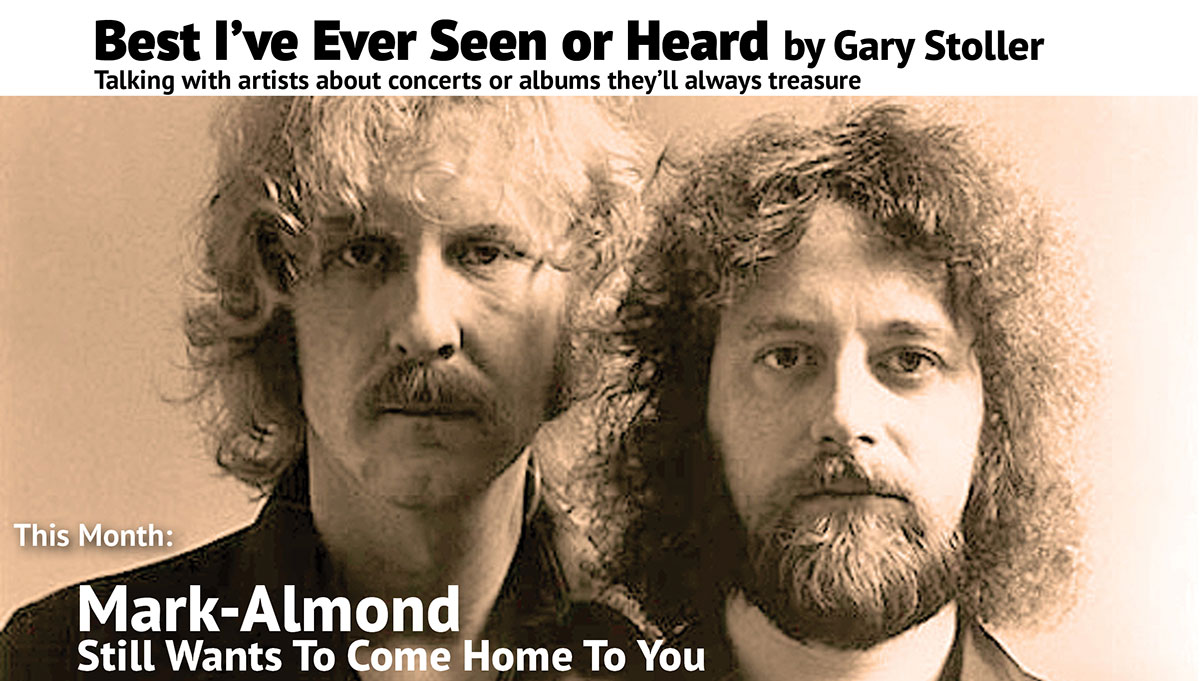

Recorded 51 years ago by Mark-Almond, also known as the Mark-Almond Band, the six-song album was the creation of two late brilliant British session musicians, Jon Mark and Johnny Almond. They met while playing in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, and I could go on and on with superlatives about their post-Mayall band that fused rock, jazz, folk and blues with a touch of the avant-garde and was a tour de force live.

I was fortunate to see the band perform live three times in the 1970s — in a tiny club in Denver and outdoors in Boulder, Colorado, and New York’s Central Park — and each performance was exciting, uplifting, thought-provoking and akin to the music on Mark-Almond 73.

Each of the seven band members plays multiple instruments on the album, and legendary keyboardist Nicky Hopkins joins them on the riveting final cut, the eight-minute “Home to You.” They were led by Jon Mark on lead vocals, lead guitar and classical guitar and Johnny Almond, whom Mark, on stage, would say played “everything.” On the album, Almond’s contributions are baritone, tenor, alto and soprano saxophone; bass, alto and concert flutes; organ; electric piano; backing vocals; timbales, and Latin percussion.

The band included two drummers and percussionists: Dannie Richmond, who played with jazz legend Charles Mingus for decades, and Bobby Torrez, a Latino jazz musician who was in Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs & Englishmen band and toured for 10 years with Tom Jones. They were joined on percussion, at times, by other band members who played a wide variety of instruments, including trumpet, flügelhorn, oboe, clavinet and 12-string and bass guitars. (Performance video link)

That’s a heck of a lot of instrumental ammunition, and it paid off in beauty, warmth and firepower in concert and on the album. And, equally impressive, all the music was wrapped among or around Jon Mark’s soft, reassuring and often impassioned vocals that drew listeners into his mind and soul.

I would rather, though, leave the accolades and insights to two people who knew Mark-Almond much better than me: Jon Mark’s close friend Eckart Rahn and his daughter Chloe Burchell.

Mark-Almond 73 shows Jon Mark’s “most honest soul coming through,” Rahn says, pointing to the album’s touching song “Home to You.”

Left my home in England

For the shores of the USA

Thinking I’d find a better way of life

But’s it’s a heavy price to pay

I spend my time drinking wine with pretty girls

I’m a loser through and through

Hear me sing this sad song

I’ve been on the road too long

And I wanna come home to you

Lived a while with a lady in New Orleans

But I phoned you every day

I was on the road, and you were home just waiting

You know that it had to be that way

Concerts every night and you know that I feel alright

But I’m so tired of paying dues

Hear me sing this sad song

Cuz I’ve been on the road too long

And I wanna come home to you

I sing this song for everyone

Who’s ever been on the road

Love is blind when you’re stoned out your mind

And every bed becomes a home

In your life, you only have but one wife

She knows what you’re going through

So hear me sing this sad song

Cuz I’ve been on the road too long

And I wanna come home to you

“For all the time I knew him, he called home every day,” Rahn says about Jon Mark, whose birth name was John David Burchell. “It’s the longest song on the album, and nothing can go wrong if you stick with your oldest friends. Nicky Hopkins’s piano keeps it all together, and Johnny, of course, was always there hovering above it.”

Mark-Almond’s music was “a rare combination of lyricism, energy, virtuosity and mindful music,” says Rahn, the president of Arizona-based label Celestial Harmonies, an imprint of Mayflower Music. Two other Mayflower imprints, Black Sun and Kuckuck Schallplatten, currently have eight Mark-Almond and Jon Mark releases for sale.

Mark-Almond “was the band that couldn’t be,” writes Rahm in the notes for the 5-CD box set Mark-Almond: Fifty Year Anniversary Edition. “It was the age of the British headliners, and they were the loudest the world had ever heard. Some had been around for a while like the Who, some were relative newcomers like Led Zeppelin. All of a sudden, a band appeared that wasn’t louder than it had to be, and they didn’t even have a drummer. But as soon as they had built an audience with their oftentimes melancholy songs where the lyrics were important and heartfelt, although a bit sentimental at times, they brought in the speediest drummer of all, the veteran of many formations around the great Charles Mingus, none other than Dannie Richmond. Still, the gentle sounds of the vibraphone and the acoustic guitars, the flutes and the flügelhorn dominated, and Mark-Almond survived for almost two decades, five vinyl albums’ worth with a few leftovers and live tracks to surface after it was all over.”

When he visited New York, Jon Mark stayed at Rahn’s apartment/office in the ASCAP building on 64th Street between Central Park West and Broadway. Rahn recalls those times and says Mark-Almond’s 1972 eight-song album Rising is his favorite.

“I had just moved in,” Rahn says. “The Rising LP was new then, and listening to the first piece with Geoff’s (Condon) flügelhorn and Colin’s (Gibson) acoustic bass, I thought I had arrived in heaven. I had played bass when I was young, but I could not ever play like this.”

After Mark-Almond called it quits in the early 1980s, Mark, who had lived for years in California, moved to New Zealand and released numerous instrumental New Age/World Music albums. One, Scared Tibetan Chant, won a Grammy for Best Traditional World Music Album in 2004.

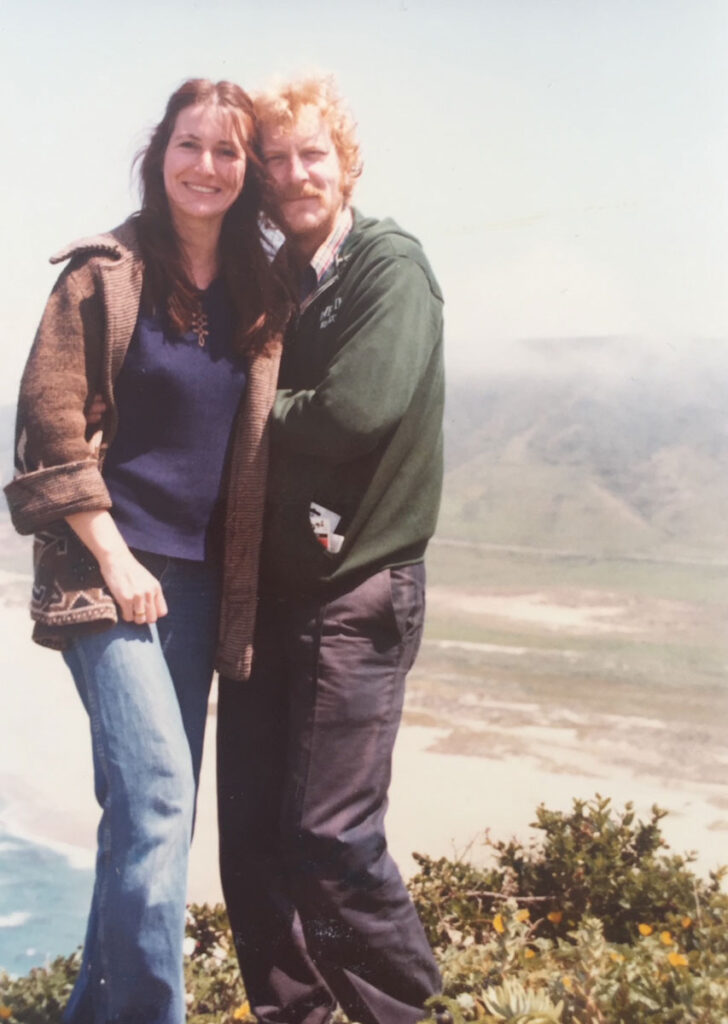

As a teenager, Chloe Burchell had many long conversations about music with her dad.

“I used to love listening to him articulate his ideas and perspectives and have many great memories of these conversations,” Burchell tells me from New Zealand. “Once his old records were shipped over to New Zealand, I used to listen to them and talk to him about them. Dad was always open-minded and listened patiently to my views about what albums I particularly liked and why. I remember playing Miles Davis, Joni Mitchell, Cannonball Adderley, Nat Adderley and Weather Report, to name a few amongst many of his old albums. He had a copy of ‘Naked & Warm’ by Bill Withers that I played so much that I forgot to remove it from the record player that was in the sun, and it ended up badly warped.”

On family car trips, Mark let each family member choose an album to play.

“Dad would invariably pick Pat Metheny.” Burchell says. “My sister would choose Steely Dan or Fleetwood Mac, and my brother played Devo. I chose Bob James’s album Three. My mother, presumably trying to pacify her three combative children, chose an album of whale sounds.”

Burchell says she “adored” her dad and loved his music.

“I grew up with a father who was always playing the guitar and singing,” she says. “Dad’s music was as natural and pleasant to my ear as birdsong. If you’re lucky enough, you’ll grow up to admire one or both of your parents, and I admired both of mine. I knew from a young age that Dad was a skilled guitar player. I remember, in kindergarten or so, telling the older boys that my dad was a better guitar player than Jimi Hendrix.”

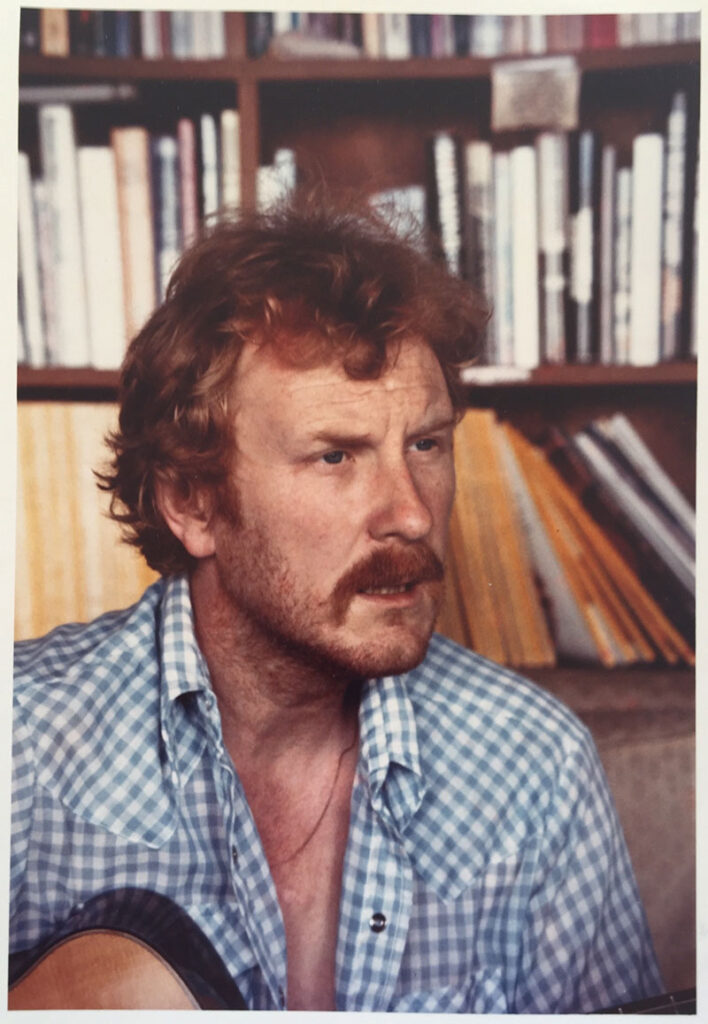

Mark told his daughter that an early music teacher inspired his love of music, and he begged his father to buy him a guitar.

“Presumably worn down by incessant nagging, Dad’s father bought him one when he was 12 or 13,” Burchell says. “When he was 15 or 16, Dad was in the merchant marines with his guitar, traveling the world and playing guitar after the day’s duties were done. On one of the voyages, Dad was tattooed — first, with an anchor and, later, with a fire-breathing dragon.”

In the mid-1960s, Mark was the music arranger and guitarist for Marianne Faithfull. He joined with Nicky Hopkins and guitar virtuoso Alun Davies in 1969 for one self-titled album in their group Sweet Thursday before he and Almond joined Mayall’s band. Mark and Almond played with Mayall on his live 1969 album The Turning Point and the 1970 studio album Empty Rooms before leaving to found Mark-Almond.

The group’s first album was self-titled and released in 1971. A year later, Mark lost the ring finger on his left hand in an accident in Hawaii, so he taught himself how to play keyboards. He continued, though, to play guitar in Mark-Amond.

“Dad told me that, after he lost his finger, he had to adapt to playing chords differently, often using his pinky finger to hold down a string or his middle finger to hold down two,” Burchell says. “It was quite a feat to be able to continue playing skillfully when he had no use at all of what was left of the ring finger on his left hand. When I was little, I would ask Dad before bed what had happened to his finger, and, every night, he would tell another tall tale about how serpents or giants took it. I would beg him to tell me the truth, but he never did.”

Burchell’s mother (Thelma Burchell) eventually told her about the accident in Hawaii. Band members were jumping from palm trees onto the beach sand, and Mark’s wedding ring caught in a lantern on the tree.

“Dad looked forward — never backward — and the loss of his finger never seemed to bother him, though it must have,” Burchell says. “He just carried on making music, because that was what he did. I now think that it must have taken considerable mental fortitude to sustain an injury that prevented him from the same level of classical playing that was his entire world and carry on as if it was nothing. If anyone mentioned his finger, he brushed it off as if it was no setback at all.”

Though Mark may not have questioned his misfortune, he ruminated about an even weightier subject in his introspective song “What Am I Living For?” on the 1972 album Rising and Mark-Almond 73.

Well I said to my best friend, can’t you see what a mess I’m in?

My daddy he taught me to drink whisky

But my momma she died from a-drinkin’ gin

My brother, he works in a coal mine, works so hard to get his pay

My sister, she believes in sweet lord Jesus

And she’s waitin’ for redemption day

What am I livin’ for?

Why am I living, why am I giving all my life

To bring up a family, children, and wife

Tell me my friend hasn’t that been done before?

While Mark’s contemplative lyrics and musicianship were a staple of the band, its sound was colored and often dominated by the skillful Almond. Besides his work with Mark-Almond and Mayall, the saxophonist and flautist played in and led London-based bands, including one with Yes drummer Alan White, and recorded with Fleetwood Mac.

“Dad used to tell me repeatedly that Johnny was a musical genius, a masterful and gifted player who could play virtually any instrument with ease and skill,” Burchell recalls. “Dad was constantly astonished by Johnny’s talent and skill.”

Burchell was similarly impressed with the talents of the original Mark-Almond keyboardist, the late Tommy Eyre, who played on the band’s first two albums but wasn’t in the band during the recording of Mark-Almond 73. Eyre, a highly regarded session player, played on recordings of numerous other musicians, including Joe Cocker, Gerry Rafferty and Deep Purple’s Ian Gillan.

“When Tommy Eyre came over to the U.S. from England, he stayed with us and spent a lot of time teaching me the piano,” Burchell recalls. “I was 4 years old. He wasn’t tutoring; he just decided to take it upon himself to teach me a little bit. He would take a pencil and write the notes on each of the piano keys so that I knew what was what. Tommy knew how to play any musical piece, including classical, and he would instruct me when to play a few keys at the top of the piano, while he played the rest of the piece at dizzying speeds. He was so brilliant and so much fun.”

In the 1980s, Eyre married violinist Scarlet Rivera, who played on Bob Dylan’s Desire album and was a member of Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue. Dannie Richmond died in 1988, and Eyre died in 2001. Johnny Almond died eight years later, and Jon Mark died in New Zealand in 2021.

Other band members, including multi-instrumentalist Roger Sutton and keyboardist Ken Craddock, have also passed, and the whereabouts of some others are unknown. The musical legacy of Mark-Almond, though, lives on.

“Some of the members have disappeared without a trace,” Rahn says. “But what hasn’t disappeared is the large audience that regroups as time goes on, fascinated by a rare combination of lyricism, energy, virtuosity and by whatever else defines Mark-Almond’s music as mindful music.”

Jon Mark left a farewell in his 1971 song “Friends” on Mark-Almond II.

So good to watch my friends dreaming their lives away

So good to watch my friends dreaming all through the day

If I could take them with me, well, you know I would

If I could show them all the things that I’ve seen, I wish I could

So sad to watch my friends growing older

So sad to watch my friends growing colder

If I could give them all some sunshine, you know I would

If I could take them all to Monterrey, I wish I could

So sad to watch my friends as they watch me

So sad to hear them talking about the things that used to be

One day perhaps I will buy myself a big boat

And take all my friends away

Maybe one day I will buy myself an island

And there with my friends you know I’ll stay

So long, old buddies, I’m going away

So long, old buddies, I’m leaving today

But don’t forget all the things that we will do

And I know you’ll spare a thought for me

I’ll say a prayer for you